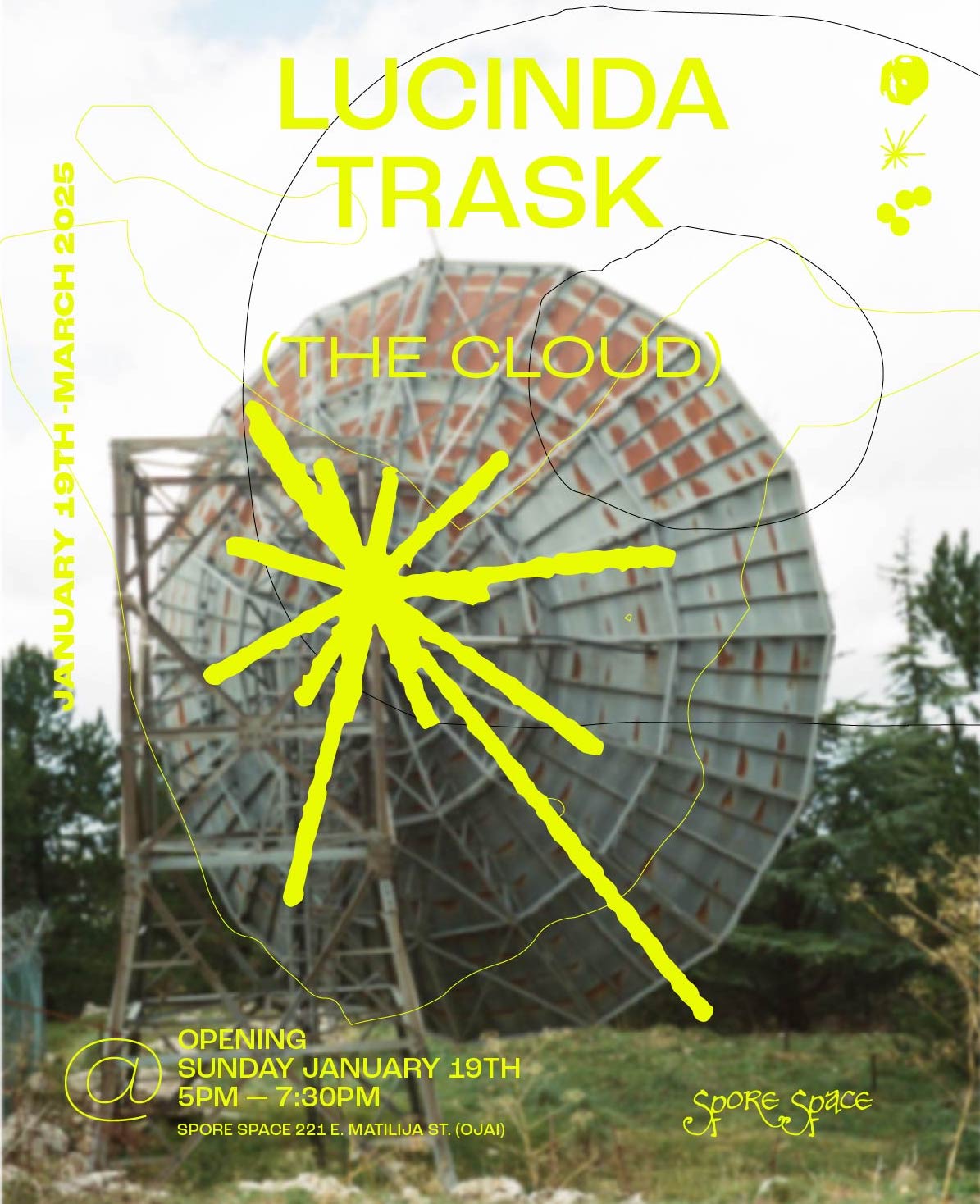

Lucinda Trask

The Cloud

January 19 - March 15, 2025

Opening Reception January 19, 5:00 - 7:30PM

Spore Space is excited to present ‘The Cloud’ by Los Angeles-based artist Lucinda Trask. Trask's new body of work explores the network of infrastructure that enables the flow of information around the globe. Her installation for Spore Space evokes a sense of intimacy, humor, and deliberation towards objects and infrastructures that operate in out-of-the-way* and complex spaces.

The exhibition lends visibility to the unseen mechanisms that make modern life possible. Calling attention to our built environment, Trask’s work examines how objects mediate our relationship to the earth through their creation and use. By giving tangible form to structures and networks which remain ethereal to most, the work aims to leave the viewer with a heightened awareness of their material surroundings – something Trask believes is essential for a mutualistic relationship with the earth.

In front of the gallery’s central window hangs a radio tower, depicted in denim appliqued on linen. The denim’s cut edges are left raw and fraying like a well-worn pair of jeans. The structure itself towers over the viewer, making these unnoticed networks of communication and connection feel pervasive and monumental. Below the curtain, a fiber optic cable made of cotton cord and denim emerges from the wall and travels across the ground, re-entering the wall and emerging from the ceiling, wiring the gallery space much the same way the planet has become connected by cables and waves. On the ground, cut black felt is meticulously intertwined and bar tacked together creating a portrait of the ocean floor rippling over the fiber optic cable. Reminiscent of a cast shadow, a rug, or a piece of lace, this piece summons a sense of familiarity and dissonance. The head of a ceramic pickaxe dangles from the ceiling—its handle has been replaced by cable—and rests inches above the floor. A tool made absurd but remaining menacing, a symbol of human impact on the earth. Trask's use of textiles throughout the exhibition makes these infrastructures, invisible through physical distance, tangible and proximate.

Lucinda Trask is a visual artist whose work, in the forms of installation, performance, sculpture, and writing, is primarily concerned with understanding how and why we shape land into landscape. Her work encourages viewers to reconsider their relationships with the inanimate matter they encounter in daily life. In 2019 Trask earned her MFA in Art from California Institute of the Arts. Since that time she has exhibited her work with REDCAT, Canary Test Gallery, Human Resources, and General Projects among others. For over ten years Trask created couture unisex garments in yearly cycles through her brand LIKE-clothing. These pieces explored a variety of themes that challenged the parameters of design, textiles, and pattern-making.

----------

*Out-of-the-way is a loaded expression, but an idea that I keep returning to. When I think about out-of-the-way places, I first think about physical distance. But of course, every location is close to somebody or something. When we are trying to keep something ugly or exploitative at a distance, who is the distance from and where does it place such sites in proximity to? I first addressed this questions in my show The Away Space which posited the sites of lumber manufacture (plantation forests and mills) and sites of object disposal (landfills, barging trash to other states or countries) as faraway places even though they are sometimes relatively close at hand. My favorite example at the time was the fact that Glendale’s landfill is in Eagle Rock provoked controversy when it was first opened.

My subsequent show, Presbyopia, tied this phrase to classical ideas around the term landscape or human “improvement” of land. This can take many forms, from growing botanical gardens that beautify land to building infrastructures which allow bodies, data and goods to flow from spaces of extraction or manufacture to spaces of use. It also includes how humans represent land in images and art. By creating pictures that keep anything we don’t want to see out of sight, we also keep those things out of mind, creating a psychological distance between ourselves and that which we deem ugly.

The idea of the out-of-the-way can also be read as political distance as opposed to geographical or mental. In this sense I am using the term out-of-the-way as out of the hands of the civic body and that specifically regarding the privatization of infrastructure. Infrastructure’s purpose is to enable a functioning society, historically funded by governments and acting as a public utility. Today most information infrastructure is being created and bankrolled by large multi-national corporations and operated as a commercial enterprise. It is no coincidence that we—both citizens and governments—are becoming increasingly dependent on an information infrastructure which is largely privately owned and maintained while democracy around the globe is beginning to break down. Private corporations are laying fiber optic cables, launching satellites into near earth orbit, and edging into the energy sector by reopening nuclear power facilities to have enough electricity to train artificial intelligence. When infrastructure is privately funded it raises myriad questions about who is profiting in its creation and use, and who will be responsible for cleaning it up when it is obsolete.

Most people do not understand how the information network functions. That it is at its heart a network of 1.5 million kilometers of fiber optic cable with an average life span of 25 years. These cables are running under the ocean, transporting data from servers and personal devices around the globe in the form of binary code, beamed down the lengths of these submarine cables as a light pulse. This pulse needs to be amplified every 46 miles, then carried to antennas, translated into a radio waves and sent through the air at a frequency which is unique to each message. This message is sent to the device of the person who requested the data. These types of systems, not to mention satellites and artificial intelligence, require huge amounts of financial, material, and temporal resources which we could be putting to other uses, or simply leaving undisturbed. The fact that these systems are spoken about in vague and ethereal terms—cyber space, the web, cloud storage, air drop—untethers them from our physical world. The Cloud seeks to reframe the landscape to include information infrastructure and thereby tie it to a material and political reality.

Text by Caroline Liou

The mythology of southern California is framed by the car window: freeways, billboards, power lines, pass by in an endless rolling landscape—we’re just along for the ride. The massive scale of industry is seen at a distance, separated by a thick pane of glass that flattens everything into just another backdrop. Lucinda Trask’s exhibition The Cloud is also framed by a window, offering a glimpse of the textile piece I climbed a mountain to scoop information out of the air (2025). Patches of yellows and blues beckon to passersby with a promise of bright skies, while thin, wiry lines stitch a hazy contour—only to reveal the silhouette of a radio tower, dramatically backlit against the interior of the gallery as the sun sets.

The exhibition makes visible the seam of things—radio towers, fiber optic cables, “the cloud”—the various forms of communications infrastructure that we take for granted, invisible, and, as the artist writes, out of the way. Trask’s works are anything but. Installed in the tiny premises of Spore Space, the two works at the center of the presentation—400 yards from shore and From elbow to fingertip (both 2025)—emerge from all corners of the room, spreading over the floor, suspending from the ceiling, penetrating through the walls. Their overwhelming materiality infiltrates the space: the velvety fuzz of felt, the loose threads of embroidery floss, the frayed hem of denim.

By translating wires, cords, and cables into textiles, Trask renders their politics material, reminding viewers that infrastructure, too, can be tangible, intimate, and pliable. In doing so, she engages in what art historian and curator Julia Bryan-Wilson describes as “textile politics,” a framework in which textiles themselves carry political meaning. Trask’s works, then, not only depict the various forms of infrastructure, but also embody its underlying set of immaterial relations and systems. Just as the denim industry implicates countless others—from its historical associations with the indigo dye trade in India and blue-collar laborers in the United States to its modern-day production concentrated across Asia and its distribution across high fashion outlets—so, too, does digital infrastructure. The virtual sphere is built on a real one, relying on industries that range from mining and energy extraction to aerospace and telecommunications. Trask’s use of craft materials—including denim, cotton, and clay— embraces these embedded histories of industry and, specifically, labor, to draw a parallel between one system of production and consumption and the next. The artist’s materiality, in other words, is an assertion in and of itself. “Part of the potency of textile politics,” as Bryan-Wilson writes, “is how stuff is able to assert itself, how things have affective, and productive, agency.” The entangled threads and frayed hems of Trasks’s soft sculptures are a direct analogy for these interconnected systems, illustrating how social fabric is simultaneously bound and unbound, subject to wear, strain, and fraying through repeated use.

If craft, as both a site of resistance and reinforcement, functions as a material means of critique against industrialization, how can representation contend with an industry largely defined by its immateriality? Paradoxically, it is through representation itself that Lucinda Trask renders these forms real again, seamlessly navigating the space between image and material through her soft sculptures. Carefully positioned to be viewed through the gallery window, I climbed a mountain to scoop information out of the air hinges on its initial presentation as an image to give way to the unexpected dimensionality of its form. Meanwhile, in 400 yards from shore, cut-out patterns evoking coral structures drape across a thick denim tube on the gallery floor, in a ripple that transforms the flat silhouette to sculptural form. Abstracted and aestheticized, her sculptures push and pull between image and material, echoing the way in which information ricochets from light pulses and pixels to wires and cables, and back again—underlining the disconnect felt in the transition between materiality and immateriality. Through her repetition of silhouetted motifs and deployment of fabric itself, Trask deliberately plays with the way in which material dissolves into image.

However, The Cloud insists on tethering the information network to its material and political reality—after all, even “the cloud” is rooted somewhere, in something. As political theorist Hannah Arendt writes, “human life…is always rooted in a world of men and of man-made things which it never leaves or altogether transcends.” Things shape human existence, just as humans, in turn, shape things. Expanding on Arendt’s writings, political philosopher Bonnie Honig specifies that it is public things—that is, infrastructure, which are crucial to our connection and therefore, any possibility of constituency—that shape a public. Fundamentally, The Cloud is an attempt by the artist to restore public things to the public, who are increasingly alienated from their means of production. Trask makes use of textiles as a uniquely relational material—meant to be worn out through repeated use, but also worn as a site of expression—to encapsulate the ambiguous relationship between things and humans. Through her material refashioning of infrastructure, Lucinda Trask reorients our relationship from one of passivity to one of agency—one that is, ultimately, an act of self-creation.

1. Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2017).

2. Ibid., 201.

3. For more on the history of craft in relation to industry, see Glenn Adamson, The Invention of Craft (London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

4. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1958), 22.

5. Bonnie Honig, Public Things: Democracy in Disrepair (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017).